This

week sees the 25th anniversary of the worst sporting tragedy in the

UK- the Hillsborough football disaster, where 96[1]Liverpool

fans died at an FA cup semi-final game against Nottingham Forest. As a mark of respect, all domestic football

matches on Saturday 12/4/14 started seven minutes late, and various tributes were held by football fans across the country. The

disaster is a scar on sporting events in the UK (and indeed on the conscience of

the nation), not just because of the scale of the tragedy, but also because of

the controversy generated in its aftermath, and the shocking injustices

experienced by the victims’ families and survivors.

This resulted in David Cameron apologizing for the 'double injustice' of Hillsborough when the report by the Hillsborough

Independent Panel

(HIP) was issued in September 2012. The fallout from Hillsborough

is still being felt 25 years on, with a new round of inquests after the quashing of the original ‘accidental

death’ verdicts in December 2012. These inquests are currently hearing

profiles of the 96 victims with some very

moving accounts by their families, and there are

also ongoing separate police and IPCC investigations

into the disaster, so the tragedy is very much in the public consciousness at

the moment. I would also argue that such disasters illustrate what can happen when crowds are viewed negatively by those charged with their safe management.

Crowd safety management- not crowd ‘control’:

It

is now largely accepted that Hillsborough was a preventable disaster, and measures have been taken since to

ensure that such crushes can never happen again (such as re-designing perimeter

fences in football stadia so that they can be opened quickly if any crushes

begin in future). However, the 1989 Taylor Report argued that it

was a miracle that such a disaster had not happened before, and highlighted the

tragic irony that before Hillsborough no-one had ever died in a pitch invasion at

a UK football match, but on 15/4/1989, 96 Liverpool fans died preventing a fictitious one. One of the things that I think is so tragic about

the Hillsborough disaster is that the way the authorities viewed football (and

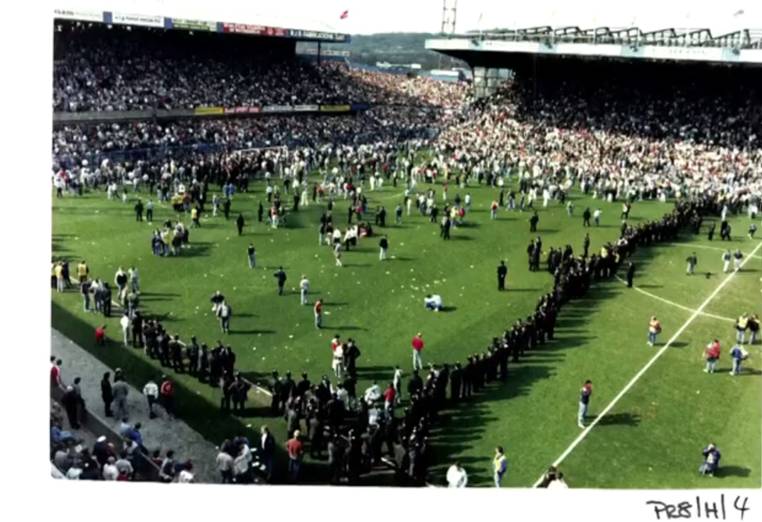

other) crowds in the 1980s influenced how they were policed, which may have contributed to the chain of events leading up to the disaster, and the lack of realisation that a fatal crush was developing until it was too late. This may also have been exacerbated by the police believing that Liverpool fans were attempting to

invade the pitch (see picture below that shows the police cordon near the

half-way line while the disaster was at its height) when in fact they were

merely trying to escape the fatal crush. A

common underlying theme emerges from this catalogue of mistakes- that football

matches (and I would argue crowd events in general) in the 1980s were all too

often seen as a potential public order problem instead of a public safety issue.

This is explicitly stated in the HIP report which concluded that at Hillsborough;

'the

collective policing mindset prioritised crowd control over crowd safety.' p.4

Myself

and others who are involved in the study of crowd emergency behaviour and

safety management are often very critical of such approaches. For instance Fruin (2002) believed

there is a clear difference between crowd ‘control’ and ‘management’;

‘Crowd management

is defined as the systematic planning for, and supervision of, the orderly

movement and assembly of people. Crowd control is the restriction or limitation

of group behavior.’ p.6

This

is not just a semantic issue either, as illustrated in John Drury’s blog post written after the HIP was

published;

‘Approaching the crowd with a view

to crowd control risks undermining crowd safety.'

Therefore,

I would argue that it is this very emphasis on ‘crowd control’ that creates an approach

to crowds that then guides how they are managed, and it was this mentality that

informed public order policing strategy at football matches in the 1980s that may have contributed to the disaster at

Hillsborough.

Police cordon at the height

of the disaster

Post-disaster

narratives of blame:

It was

not just the disaster itself that made Hillsborough infamous, but also the subsequent attempts to deflect blame for the tragedy onto the victims that

have so hurt their families and survivors, resulting in an enduring sense of

injustice that is still felt today. However, I also think that the lies that

were disseminated about the fans' alleged behaviour (which have since been shown

to be totally without foundation) were all too readily accepted by politicians

and the media, and this was influenced by a pervasive (but largely false[2])

view in society that crowds are not to be trusted because of their

potential for ‘irrational’ behaviour.

The most notorious example of these was perhaps the false allegations that appeared on the front page of the Sun newspaper, under the headline ‘The Truth’ four days after the disaster. I would argue that such irrationalist views of crowds also permeated to the very top of the British establishment, as highlighted by reports that senior police officers briefed the then Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher days after the tragedy that drunken Liverpool fans were to blame for the tragedy, despite there being no evidence to support this claim. Margaret Thatcher’s chief Press Secretary Bernard Ingham also provoked outrage by defiantly sticking to the myth that Liverpool fans were to blame and the city should ‘shut up about Hillsborough’, and Boris Johnson was recently forced to apologise for an article that appeared in The Spectator magazine when he was editor, that falsely blamed drunken fans for the tragedy. This has all exacerbated the sense of injustice, and a recent article in the Daily Telegraph looks at the shocking treatment of victims after Hillsborough, arguing that derogatory stereotypes of Liverpuddlians have also helped contribute to the enduring myth that somehow fans were to blame.

The most notorious example of these was perhaps the false allegations that appeared on the front page of the Sun newspaper, under the headline ‘The Truth’ four days after the disaster. I would argue that such irrationalist views of crowds also permeated to the very top of the British establishment, as highlighted by reports that senior police officers briefed the then Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher days after the tragedy that drunken Liverpool fans were to blame for the tragedy, despite there being no evidence to support this claim. Margaret Thatcher’s chief Press Secretary Bernard Ingham also provoked outrage by defiantly sticking to the myth that Liverpool fans were to blame and the city should ‘shut up about Hillsborough’, and Boris Johnson was recently forced to apologise for an article that appeared in The Spectator magazine when he was editor, that falsely blamed drunken fans for the tragedy. This has all exacerbated the sense of injustice, and a recent article in the Daily Telegraph looks at the shocking treatment of victims after Hillsborough, arguing that derogatory stereotypes of Liverpuddlians have also helped contribute to the enduring myth that somehow fans were to blame.

Margaret

Thatcher visiting Hillsborough after the disaster with senior police officers,

Home Secretary Douglas Hurd, her Press secretary Bernard Ingham, & other Tory politicians

Conclusion:

There

is almost a sense of moral panic in the way society views crowds, in that they

are often seen as vehicles for potential ‘disorder’ or mass ‘panic’, despite

over 30 years’ worth of research into crowds by psychologists[3]

finding that such concepts are largely myths & that crowds often behave

much more sensibly than they are usually given credit for. When tragedies happen,

it is usually because of a failure of crowd management techniques (as

opposed to any ‘irrational’ behaviour on the part of the victims), and attempts

to blame victims are often part of a strategy to deflect blame away from those

responsible for such mismanagement. I have argued in a previous blog

post that using emotive terms such as ‘panic’ to describe victims’

behaviour in disasters can serve such attempts to shift blame. I think that

this deep societal mistrust of crowds was a major contribution to the context in

which Hillsborough happened, and why the despicable slurs that were spread about the victims

were allowed to remain unchecked in popular discourse for so long- which no

doubt added to the pain and distress of those who knew the truth about what

happened. Therefore, in order to help avoid future Hillsboroughs I think we need

to develop a less negative view of crowd behaviour in popular discourse, or as I concluded in my blogpost

when the HIP report was released;

‘we all need to take responsibility for ensuring that we adopt a

less pathological view towards crowds, and try to develop crowd safety

strategies at large events that prevent such disasters from ever happening

again’

References:

Cocking, C. & Drury, J. (2014) Talking about

Hillsborough: ‘Panic’ as discourse in survivors’ accounts of the 1989 football

stadium disaster. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 24 (2) 86-99. DOI: 10.1002/casp.2153; http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/casp.2153/abstract

Fruin, J. J. (2002). The causes and

prevention of crowd disasters. Originally presented at the First

International Conference on Engineering for Crowd Safety, London, England,

March 1993 (Revised exclusively for crowdsafe.com, January 2002.)

[1] 95 died on the day, and one was left

in a persistent vegetative state, dying nearly 4 years later

[2] My blog attempts to correct the common

myths that are often perpetuated in the media/ popular discourse etc; http://dontpaniccorrectingmythsaboutthecrowd.blogspot.co.uk/

[3] See Drury

(2014) for a recent overview of the study of the psychology of crowd

behaviour

Calm, orderly, and sane as ever Chris! Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteYour expert opinion would be valuable on the recent Prefectoral decision to obstruct the traditional route of a march through Nantes. In my view was designed to foment conflict, not facilitate lawful demonstration: http://juliusbeezer.blogspot.fr/2014/02/dont-want-new-airport-tear-gas-for-you.html

Have you got any pointers/references to good practice for authorities anticipating large demonstrations? (A police manual? EU guidelines? ??)

Three people lost eyes to rubber bullets in the ensuing confrontations, and this issue won't be going away anytime soon: http://www.politis.fr/La-police-nantaise,26497.html (Fr)

Thanks for your interest. I'm not aware of a manual for European public order policing as approaches may vary across countries, but the British Police have published their own guide on how they manage public order situations, which is available on-line;

Deletehttp://www.acpo.police.uk/documents/uniformed/2010/201010UNKTP01.pdf