Brighton is counting the cost of another protest by the March for England (MfE) on Sunday 27th April 2014. So far, there have been a reported 27 arrests and some local businesses were damaged during scuffles in the city centre as anti-fascists confronted them. The MfE attracted an estimated 100-150 and they were opposed by at least 1000 counter-protestors. As happened last year, Sussex Police conducted a massive operation to police the march and counter demonstration, with Superintendent Steve Whitton quoted as saying that up to a dozen different forces were involved, including officers from: Surrey, Hampshire, Dorset , Kent, Devon & Cornwall, City of London Police (CoLP) , the Metropolitan Police (MPS), and Thames Valley Police (TVP). A Police helicopter, eight horses and dog units were also in attendance, so estimates that costs of the policing will run to at least £1/2million seem realistic given the resources they had available on the day.

As happened in 2013, the MfE were allowed to march along a stretch of the seafront road, with barriers and police vans separating the two sides. However, there were also serious scuffles between counter-protestors and police as they headed north back to Brighton station afterwards, with horses being used to push the crowd back down Queens road. This has some similarities with the march in 2012, as it was on Queen's road where the Police had to cut the MfE march short and divert it through back streets because of the level of opposition they faced. Prior to this year's march, there had been speculation that the march might be cancelled or re-routed at the last minute because part of the road on the route along the seafront collapsed, leading some to Tweet that 'even the road don't want fascists on them'! However, other than announcing a slightly amended-route on 25/4/14, Sussex Police allowed the march to go ahead despite massive local opposition, including a unity statement signed by local trade unions, the local MP- Caroline Lucas, and most of the Green councillors on Brighton Council.

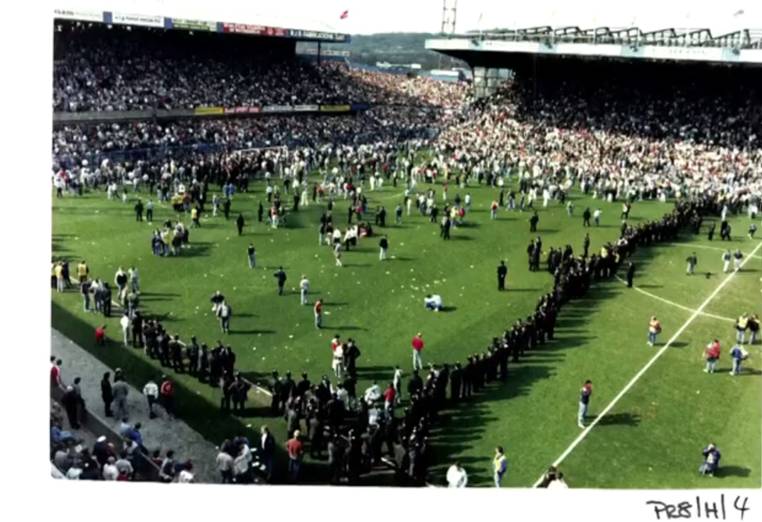

March for England protestor confronts counter-demonstrators

Use of public order legislation:

There was however, a noticeable difference in how the POA was implemented when compared to how it has been used against other anti-fascist protests. For instance, I explored in a previous blog in September 2013 how nearly 300 anti-fascist protestors were arrested en masse under the POA while protesting against an EDL march in London. While Sussex Police invoked Sections 12 and 14 of the POA this Sunday (which meant they could place temporal and spatial restrictions on the march and any counter-protests), no mass arrests happened, and local media have reported just one person as having been arrested under these sections of the POA. Why this happened is a matter of speculation, but I would suggest two possible reasons (although I'm sure there could be others).

Firstly, the fluid nature of the situation (especially when crowds were blocking the route of the March for England North to the station), may have meant that it was not practical (or even feasible) for the police to have conducted mass arrests in central Brighton on a busy Sunday afternoon- whereas the MPS had created a large sterile area for the EDL protest in London in September 2013, and it was easier to detain people en masse within this space (especially as this area was close to the City of London, which was largely empty on the Saturday afternoon that the protest happened).

Secondly, it's possible that the police were wary of making arrests under the POA because of Caroline Lucas's recent acquittal in Court after being arrested at the fracking protests in Balcombe last August. She had been charged under S.14, but it emerged in Court that the police had made mistakes in issuing the necessary conditions and directions, as illustrated by local journalist Ruth Hayhurst;

The district judge at the trial of MP Caroline Lucas and four other anti-fracking campaigners said conditions imposed on people at the Balcombe protest on August 19th were unlawful. He said the senior police officer who issued the conditions was not authorised to do so, he was wrong to issue them and they were so vague and unclear as to be meaningless.

Therefore, perhaps Caroline's recent victory meant that Sussex Police were reluctant to make fresh arrests under the same legislation, in case a similar verdict was reached in future trials arising from any mass arrests. She was also visibly present (see photo below) in the pen that was designated by the police as the 'authorised' protest area under S.14, so maybe she scared them off from making a repeat performance!

Caroline Lucas in the Section 14 pen (from demotix.com)

Wider context of the POA:

'The criminal law acts to de-contextualise the behaviour of individuals from the social context in which that behaviour took place [ ]. The social context in which actions take place ought, however, to be entirely relevant when assessing the ethics of an individual's actions' p.16

Conclusion:

Events such as the March for England can create a great deal of disruption, and the opposing perspectives held by the different groups involved are not easily reconciled. For instance, the MfE seem determined to continue requesting permission to march in Brighton (despite the fact that the vast majority of the local community do not want them to do so), and the police claim that they are duty bound to facilitate them if they are approached. I would argue that it is a little disingenuous for the police to make this claim, as such an approach is predicated upon a rather selective interpretation of minor sections of the POA, and that in other situations, more serious public order legislation is often invoked if it suits their aims and tactics. I'm not saying the situation will necessarily be resolved if the police started mass arresting MfE protestors next time they appear at Brighton's city limits (and I imagine some counter protestors would probably prefer to oppose the MfE themselves, rather than relying on the police). However, specific problems associated with the MfE coming to Brighton, and the wider social contexts in which such groups can emerge, need to be considered, as solutions are unlikely to found by merely relying on the selective (and sometimes politicised) use of controversial public order legislation.

N. El-Enany, (In Press) ‘The criminalisation of the right to protest’, in F. Pakes and D. Pritchard (eds.) Riot: Unrest and Protest on the Global Stage. Palgrave Macmillan.